Fagong 发功: Significance and Historical Evidence

Fagong 发功, the skill of emitting qi, is a diverse topic as it actually has quite a long history in China, there are many types of qi emission, and there are various reasons why this skill might be something to pursue.

Historical Evidence of Qi Emission

Qi emission, or faqi 发气, can be a controversial subject and, for the most part, in China has been taboo to demonstrate or speak of too publicly since well before the internet was around. So although it is something that exists among neigong adepts in China, you won’t find demonstrations or much about it on Chinese internet or social media. Interestingly, records of qi emission, previously referred to as buqi 布气, can be found in historical Chinese literature as well as in local gazetteers (difang zhi 地方志) which are a primary source for the study of China’s local history.

Su Dongpo, who lived during the Song Dynasty, is one of the most famous poets of all time (among other talents) in China. He left a collection of personal essays in his anthology titled Dongpo Zhilin 東坡志林, which chronicled many of his personal encounters including one involving qi emission therapy.

學道養氣者

至足之餘

能以氣與人

都下道士

李若之能之

謂之布氣

Those who study the Dao and cultivate their qi, when they have enough qi, they can pass onthat extra qi to other people. In the capital, there is a Daoist called Li Ruozi. He can do ít. He calls this therapy ‘buqi’ 布气 (‘Qi Emission’).

Su Dongpo then continues to tell the story of when he took his second son Dai to get healed by the Daoist Li Ruozi. It involved a contactless form of qi emission in which the two sat across from each other and the recipient, Su Dongpo’s son, felt a warmth in his belly “as if the morning sun was shining on it” (如初日所照温温也).

There are many other accounts of various types of qi emission therapy throughout China’s history in sources such as the local gazetteers. Another notable example involved a Daoist called Mountain Man Yi 尹山谷 in the Yuan Dynasty who appears in multiple books and gazetteers. In one account, to heal a child that is on the brink of death, Mountain Man Yi performs a type of qi emission in which he tied his feet to the child’s feet and emitted a massive amount of qi out from the yongquan points on the bottoms of his feet into the child’s. This type of qi emission cost him 10 years of his gongfu, but was able to save the child’s life.1

Types of Qi Emission

There are many types of qi emission that can range from the more subtle and difficult to detect to very palpable forms with an undeniably strong physical reality. Naturally, where the former give much more room for skepticism, the latter include forms that force those experiencing it to confront the physical reality of what many thought was something that only existed in movies and kung fu fantasy stories. It is important to note though, that faqi need not be the strongly felt and obviously observed type to be real. Consider the example of the Gengmenpai masters who are famous for their very palpable forms of electric-like qi emission which they use for medical therapy. Within the same healing session in which they are using the strong, electric-like waiqi 外气 (“external qi”) emissions, they will also use a different type of emission which they explain as rather working with neiqi 内气 (“internal qi”). The neiqi is not felt at all by the average person, yet it is very important and has real observable effects when used, for example, to push stagnant blood to a point on the body from which it is extracted, or to open acupoints to facilitate emitting/receiving waiqi.

Purpose of Qi Emission

There are also many different purposes for the use of qi emission. One of the most common is for qi emission as medical therapy which is a very understandable and useful application. Another application is as a part of advanced martial arts skill used for self-defense. It is also possible to cultivate different types of qi that can be used in applications of Daoist medicine which may involve talismans and the use of qi to imbue qualities of protection, cleansing, good fortune, etc.

Significance of Qi Emission

Another, perhaps more modest but equally important reason for developing the skill of qi emission also relates to its significance in and of itself as a signpost for the practitioner. This reason specifically involves the type of qi emission that is strongly felt, such as a tangible bioelectric current that has the power to involuntarily contract muscles in people and move physical objects such as small cut-up pieces of paper or cigarette ash (objects typical for beginners to practice on). The first time this type of qi emission is performed it demonstrates to the practitioner themselves both the achievement of a certain level of neigong development as well as an undeniable demonstration of proof that neigong/qigong practice can in fact lead to significant energetic achievements. When you feel this sort of qi emission (or even better, are the one performing it), there is no room for doubt that qi emission is something that is very real and capable of strong effects. Sure, there are other signs that a practitioner can experience to show that qigong is real and really doing something, but it’s hard to think of others as immediate, dramatic and undeniable as this. Subtle signs are much more easily explained away. This is something that could only be explained away via some sort of grand conspiracy involving professional-level magic tricks, hidden electrical devices, elaborate planning, and use of co-conspirators–in most cases to the point where any “debunking” explanation becomes much too far-fetched (and I am speaking here of “explaining away” just from the perspective of onlookers and recipients of the qi emission).

The benefit of performing this skill for a practitioner to prove to themselves and others who were present that it exists is not at all insignificant given the predominant worldview that tells us that qi emission and other skills like this are not possible. This prevalent skepticism, which extends even to skepticism and disparaging views towards the entire system of thought that qigong and Chinese medicine are founded on, is a real barrier for many people to even be open to the idea of practicing qigong, let alone maintaining a level of morale towards practice that can push them through the years of daily drudgery typically required to make significant achievements in the practice.

Qi emission can be considered a siddhi by some, even though it is not generally included in the standard listings of siddhis such as the Six Pervasions (aka the “Six Shen Powers” Liu Shentong 六神通). The former doesn’t really challenge a materialist/physicalist conception of reality whereas the latter certainly do. Qi emission, such as the strong bioelectric type, then is more of an exceptional display of the limits of human potential, a rare level of human energetic development, something that we didn’t think humans were capable of. It certainly shouldn’t be called “supernatural” (a term that itself is very problematic and also particularly triggering for skeptics). I think a better term would be “paranormal” or maybe “supernormal.”

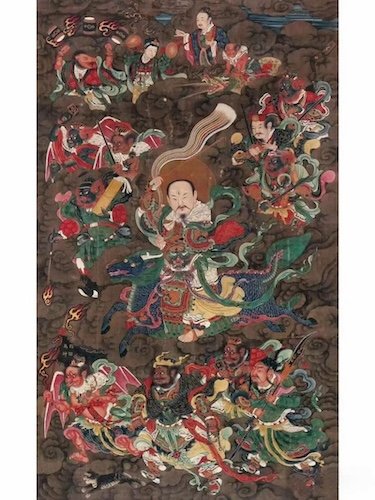

How you view it depends on how you frame it, as well as on your underlying conceptions of reality. On the one hand, the electric-like qi emission could be made to seem somewhat mundane by citing that it’s no big deal because it is similar to what some aquatic animals can do when they generate strong bioelectric shocks. On the other hand, you can look at it from a perspective that says that by enacting this skill one is essentially learning to wield the most raw forces of nature and bend them to one’s will without relying on sophisticated tools and machinery, but rather through the use of a combination of mental intention and some sort of physiological mechanism in humans not yet known to science. Looked at more poetically, bioelectric qi emission is the use of one’s will to generate what would essentially be the force of lightning from within the microcosm of the human universe (i.e. the human body-mind). Lightning has deep symbolism within spiritual traditions, including of course the Chinese spiritual traditions ranging from Shaolin’s patron saint Vajrapani (who’s name means “Wielder of the Thunderbolt”) to the Daoist Leifa 雷法 (“Thunder Rites”) traditions.

Any discussion of faqi or other “powers” wouldn’t be complete without the disclaimer that skills like this are just that, skills, or when not specifically directed towards useful applications–merely byproducts of successful training. They should not be mistaken for some indispensable facet of a spiritual path. Practitioners should deal with such things in a skillful manner and not develop attachment to such skills.

References

1. Lok, L. Qi Emission Therapy. Online Course. https://vooma.thinkific.com/courses/qi-emission (for historical evidence of qi emission)