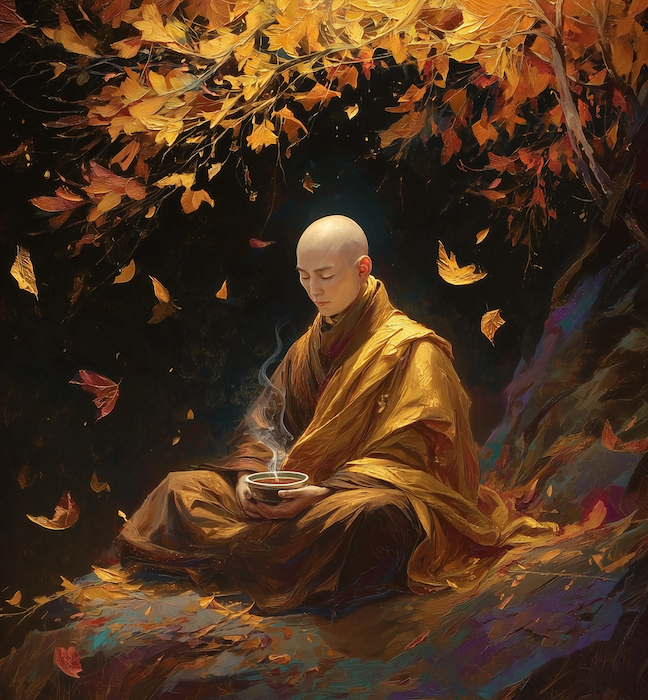

Tea and Zen, One Taste 禅茶一味

The famous saying Chan cha yi wei 禅茶一味 means that tea and Zen are the same (lit. Zen and tea, one taste). This illustrates the fact that Zen practice is not bound to the meditation cushion, but should necessarily be integrated into daily life: “meditation in action.” The tea ceremony can then become a vehicle for practicing Zen.

The character for Zen in Chinese is Chan 禅 (禪). “Chan” is a transliteration of the Sanskrit word dhyana (jhana) which is a form of meditation that involves profound concentration and deep absorption on a singular object of meditation. The word can be broken down into dhi (mind) + yana (vehicle). The particle 礻which looks like a person bowing down, represents a person worshiping at an altar. The other component 單 pronounced “dan,” refers to an individual (a single person), and brings in implications of “single,” “solitary,” “unitary,” “monad.” Putting the parts together we can derive an interpretation: worshipful single-pointed concentration; focus on a single thing (and the underlying unity of all things).

Chan is both a process and a result.

The Chinese character for tea (cha 茶) is composed of the character for “person” (ren 人) situated between the grass radical (cao 艹) and the character deng (朩), which is derived from the character for wood or trees (mu 木), suggesting a person in nature, perhaps picking leaves from trees. The human being integrating with nature is a central theme, and even an ultimate pursuit, for both Chinese Buddhism and Daoism.

In both traditions practitioners seek to let go of their egos, which identify them as separate, individuated beings, and get in touch with the mysterious source of existence that both underpins and constitutes all of nature as well as humans themselves. Present in/as/through every person, this is what Buddhists call Buddha Nature (fo xing 佛性) and Daoists call Dao (道). Zen (Chan) advocated closely observing one’s own mind to attain realization of one’s original nature (性), and the importance of seeking Zen in ordinary, day-to-day activities was a common theme. So applying Zen practice to the cultivation, picking, processing, preparing, and drinking of tea was natural for Chan monks.

Our “original nature,” also referred to by Buddhists as our “original face” (and corresponding to the “primordial spirit” yuanshen 元神 referred to by Daoists), is that base root of our raw consciousness: radiant and numinous awareness. Distinguished from the thinking and discriminating mind that reaches out through our senses and can get so easily lost in mental rumination, it is just the bare, awake, observant, non-differentiating consciousness that already naturally exists prior to our engagement with the outside world, thoughts, and imagination. The process of cultivation seeks to help us uncover and live through this “original face” and abide in it in a sustained way. But to go directly to that is extremely difficult, and this is why there are techniques and practices that can bring a practitioner gradually towards that deeper layer of their being, so that they can fully access the Buddha Nature within.